Iran is anything but crazy: Rational theology and strategic doctrine of waiting in the Islamic Republic

The nuclear thinking behind the nuclear thinking

On a spring day in Tehran in 1979, as the dust of the revolution was still settling, Ayatollah Ruhollah Khomeini stood before the newly formed Islamic Republic to outline his vision.

"In the Islamic Republic, everything that exists in Iran today must be changed," he declared. "Our universities must be changed, the dependent universities must be converted into independent universities. Our education must be changed, our colonialist culture must be converted into an independent culture."

These words would herald a fundamental transformation – not just of Iran's institutions, but of the very relationship between religion and governance. This transformation embodied a worldview profoundly different from the Western understanding of how faith and state should interact.

Many Western observers dismiss Iran as a "crazy" or "irrational" actor on the global stage. This characterization fundamentally misunderstands the nature of Iranian statecraft. Far from lacking rational decision-making, the Iranian regime operates with careful calculation and strategic coherence. The key distinction lies not in Iran's capacity for reasoned action, but in its fundamentally different framework for understanding reality – one rooted in a theological worldview often unfamiliar to Western analysts. What appears as irrationality to Western observers is, in fact, the product of a sophisticated and internally consistent system of thought, one that merges religious doctrine with political strategy in ways that challenge secular Western assumptions about how states should behave.

Separation of mosque and state?

Western analysis of Iranian policy often falters by imposing familiar paradigms of church-state separation onto a fundamentally different political-theological framework. While Western governance maintains clear boundaries between religious and political spheres, the Islamic tradition – particularly in its Shiite manifestation – emerged from, and maintains an intrinsic unity between spiritual and temporal authority. This unity isn't merely theoretical; it demands practical expression through concrete political and social action.

What appears as irrational or Messianic fervor to Western observers often represents sophisticated theological-political calculation in Iranian statecraft. As Iran navigates complex regional dynamics in 2024, including recent setbacks in Syria and challenges to its proxy network, understanding the deep theological foundations of Iranian power becomes more crucial than ever. This evolution of Shiite thought provides an essential context for interpreting Iran's current actions and anticipating its future moves.

Unlike Christianity's early separation from political power under Roman rule, Islam developed as an integrated system where religious authority naturally encompassed governance. Muhammad's simultaneous role as spiritual guide and political-military leader established a template where theology and statecraft were inseparable, and more importantly, where theological principles demanded practical implementation.

This fundamental difference traces back to the foundational teachings of these faiths. In his final commands to his disciples, Jesus focused solely on spreading the message of God's kingdom, with no mention of establishing political dominion. Similarly, rabbinic Judaism, developing after the destruction of the Second Temple, emphasized spiritual and ethical development rather than political power. These theological foundations profoundly shape Western political thinking, making it difficult for Western analysts to fully grasp Islamic political theology, where religious and political authority are intrinsically unified. This disconnect often leads Western observers to misinterpret Iranian strategic decisions through an inappropriate secular lens.

Understanding how this plays out in Islam is a major undertaking, so in this article, I will attempt to demonstrate this phenomenon only in Shiite Islam and the Islamic Republic of Iran that adheres to it.

Historical foundations: The formative crisis

The death of Muhammad in 632 C.E. catalyzed developments that would shape centuries of Shiite political theology. The belief that leadership should pass through Muhammad's family line through Ali ibn Abi Talib represented more than a mere succession dispute – it embodied a comprehensive theology of authority and legitimacy that continues to influence Iranian policy today.

The events at Karbala in 680 C.E. stand as perhaps the most traumatic moment in Shiite history. Husayn ibn Ali, grandson of Muhammad, along with his small band of family members and loyal followers, found themselves surrounded by a massive army serving the Umayyad Dynasty.

The Umayyads were the ruling family who had seized control of the Islamic world following a series of political maneuvers that had pushed Muhammad's own family aside. To Shiite believers, the Umayyads represented the triumph of worldly power over divine right - they were seen as usurpers who had transformed Muhammad's religious movement into a mere empire, replacing spiritual authority with naked political ambition.

What followed on those sun-scorched plains of Iraq was not merely a military defeat - it was a shocking betrayal that would reshape Shiite consciousness forever.

The Umayyad forces cut off water supplies to Husayn's camp for three days, forcing them to watch their children suffer from thirst under the merciless desert sun. One by one, Husayn's male relatives and supporters were cut down in combat. Finally, Husayn himself was killed, and his head was carried on a spear to Damascus as a trophy. The survival of his sister Zaynab, who was forced to march as a captive to the Umayyad court, ensured this tragedy would be seared into collective memory through her eloquent testimonies of grief and defiance.

Rather than triggering an immediate violent revolution, this devastating event led to what scholars describe as a profound "loss of heart" among many followers of the Ahl al-Bayt (Muhammad's family). The shocking reality that the grandson of Muhammad could be so brutally slaughtered by fellow Muslims - and that the broader Muslim community had stood by in silence - forced a fundamental reassessment of how divine justice would be achieved in this world. This seemingly total defeat paradoxically produced a sophisticated reorientation of Shiite thought that emphasizes patient, strategic action over impulsive response - a principle that continues to guide Iranian strategy today, where perceived betrayals and setbacks are interpreted through the lens of Karbala's ultimate vindication.

After Karbala, Shiite leaders made a decisive strategic shift. Rather than pursuing doomed rebellions, Muhammad al-Baqir and Jafar al-Sadiq built enduring religious institutions and legal frameworks. This was not surrender but strategic adaptation – one that modern Iran's leadership explicitly references when justifying their own measured responses to provocations. As Iran's Supreme Leader Khamenei noted in a 2019 address: "Like our great Imams, we understand that patience in the face of apparent defeat can lead to ultimate victory."

The Doctrine of Occultation: Strategic framework for modern power

The disappearance of the twelfth Imam in 873 C.E. represents another pivotal trauma that would fundamentally reshape Shiite theology and practice. Muhammad al-Mahdi, the five-year-old son of the 11th Imam, vanished under mysterious circumstances just as hopes were mounting that he would finally restore divine justice to a world that had persecuted his forebears. For a community that had endured centuries of defeats by maintaining faith in an eventual triumph through their divinely guided Imams, this disappearance threatened spiritual catastrophe.

The initial response was desperate denial. Many refused to accept that the line of visible Imams had ended, claiming the young Mahdi was merely in hiding and would soon return. As weeks turned to months and months to years, the community faced an existential crisis: how could they maintain their identity and purpose when their divine guide, the very anchor of their religious worldview, had vanished?

Yet remarkably, rather than fragmenting the community, this crisis was transformed through sophisticated theological interpretation into a powerful framework for patient but purposeful action. The concept of occultation (ghayba) was developed to explain that the Imam had not abandoned his followers but had been deliberately hidden by divine will until humanity proved worthy of his return. This apparent disaster was thus reframed as a test of faith and an opportunity for the community to prove its worthiness through steadfast preparation.

This theological-political framework developed into several branches. Twelver Shi'ism, which dominates in Iran and Iraq, represents the majority of Shia Muslims. While smaller sects like the Ismailis and Zaydis share the belief in Ali as the first rightful successor, they diverge on subsequent succession – Twelvers following twelve Imams with the last being the Hidden Imam, while others recognize different lineages. Each developed distinct interpretations of Islamic law.

Twelver Shi'ism continues to shape Iran's modern approach to power projection, where apparent setbacks can be interpreted as opportunities for demonstrating steadfast dedication to ultimate divine justice. When modern Iranian leaders speak of the hidden Imam, they tap into centuries of accumulated meaning around patient endurance and strategic preparation in the face of seemingly overwhelming odds.

The occultation period was divided into two phases:

1. The Lesser Occultation (873-941 C.E.): Maintained community cohesion through designated representatives

2. The Greater Occultation (941-present): Established broader clerical authority and frameworks for collective action

This historical development helps explain why Iran's Supreme Leader can exercise broad authority while maintaining theoretical subordination to the hidden Imam – a sophisticated balance of practical power and theological legitimacy. More on that later.

Intizar: The Doctrine of Active Preparation

The concept of intizar (waiting) in Shiite theology represents one of the most misunderstood aspects of Iranian strategic thought in Western analysis. Initially conceived as a state of expectancy for the reappearance of the Hidden Imam in Twelver Shi'ite belief, it embodied a doctrine of hope and trust in the eventual establishment of an ideal Islamic society.

However, the concept experienced a profound shift in the 20th century through the interpretations of thinkers like Murtaza Mutahhari, who transformed it from a passive state of waiting into an active revolutionary principle. In this modern understanding, the Mahdi's advent was reframed not as a sudden occurrence but as the culmination of an ideologically driven revolution requiring believers' active participation during the Occultation. This reinterpretation effectively legitimized the establishment of a just state as a stepping stone toward the Mahdi's final revolution.

Rather than passive anticipation, the evolved understanding of intizar demands active preparation through concrete measures:

- Building military and economic strength

- Establishing strategic depth through regional alliances

- Developing systems for implementing Islamic law

- Creating networks of supporters across the Islamic world

As Ayatollah Khomeini declared: "If a person who waits for Faraj [the emergence of the Mahdi and the establishment of divine justice] thinks that he should only pray without having any other obligations, then he is not a true Muntazir [one who actively waits and prepares] for the Mahdi's return, even if he acts upon his own Sharia obligations." This statement emphasizes that merely following religious law while passively waiting is insufficient – believers must actively work toward establishing the conditions for divine justice.

Modern manifestations: Strategy through a theological lens

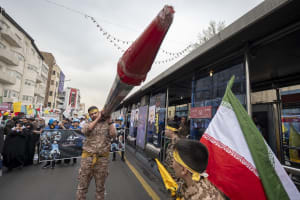

Recent developments in the Middle East illustrate how this theological framework shapes Iranian strategy. The "Ring of Fire" approach developed by General Soleimani represented more than military encirclement - it embodied theological principles about preparing for and protecting the faithful during the period of occultation.

The recent collapse of Assad's regime in Syria and the degradation of Hezbollah's capabilities present significant challenges to this strategic framework. However, Iran's response demonstrates the system's adaptability while highlighting its constraints. Rather than reactive escalation, Iran's measured response reflects centuries of theological evolution emphasizing strategic patience and calculated action.

Velayat-e Faqih: Modern innovation in traditional framework

Ayatollah Khomeini's doctrine of Velayat-e Faqih (Guardianship of the Islamic Jurist) represents the culmination of centuries of theological development regarding authority during the Mahdi's absence. This concept, which forms the constitutional foundation of modern Iran, establishes that in the absence of the Mahdi, a supreme religious scholar can serve as guardian of the Islamic community, wielding both spiritual and political authority.

The sophisticated theological foundations of Velayat-e Faqih can be traced to the interpretation of even the briefest religious texts. Perhaps the most remarkable example of how seemingly minor statements could spawn centuries of political theory lies in Muhammad's deceptively simple prayer: "Oh God, mercy upon my successors." These five words – barely a breath in the vast corpus of Islamic teachings – would become a theological lodestone for generations of Shiite scholars, culminating in Ayatollah Khomeini's revolutionary interpretation.

Like constitutional lawyers finding entire frameworks of governance in the sparse text of founding documents, Shiite theologians would mine this brief supplication for layers of meaning about succession, authority, and legitimate rule. Khomeini would later seize upon this simple prayer as evidence for his doctrine of Velayat-e Faqih, arguing that Muhammad's concern for "successors" – not merely "successor" – implied a continuing line of religious governance extending beyond the Imams. This interpretive expansiveness would prove particularly crucial as Shiite scholars developed increasingly sophisticated frameworks for religious authority in the absence of direct prophetic or imamic guidance.

The doctrine resolves a crucial question in Shiite theology: how to govern legitimately while awaiting the Mahdi's return. Under this system, the Supreme Leader (currently Ayatollah Khamenei) derives his authority from his religious expertise and moral character, acting as a temporary guardian until the Mahdi's return. This creates a sophisticated balance where immediate political decisions can be made while maintaining ultimate theological loyalty to the hidden Imam.

As Khomeini himself explained in his book Islamic Government (1970): "The governance of the faqih [religious jurist] is not an ordinary government. It is the implementation of Islamic law, a system that takes precedence over all secondary ordinances such as prayer, fasting, and pilgrimage." This framework provides religious legitimacy for state actions while establishing clear parameters for decision-making, creating a flexible but theologically grounded system for actual governance.

The practical implications are far-reaching. The Supreme Leader can declare war, negotiate peace, establish foreign policy, and make economic decisions – all while maintaining that these actions serve the ultimate purpose of preparing for and protecting the community until the Mahdi's return. This system allows Iran to engage in modern statecraft while maintaining its theological foundations.

When the war room and the waiting room mix

Iran's approach to power projection reflects a sophisticated theological framework that fundamentally differs from Western strategic concepts. Where Western strategy often operates on immediate timeframes of victory or defeat, Iranian strategic thought embraces a much longer view shaped by centuries of theological evolution.

This means that what appears to Western observers as periods of peace or ceasefire may represent, to Iranian strategic planners, merely phases in a continuing theological-political struggle. The concept of active waiting - patient preparation combined with strategic flexibility - creates a framework for sustained action that transcends immediate setbacks or victories.

Understanding this theological architecture of Iranian power doesn't require accepting its premises, but it demands recognizing its internal coherence and direct influence on decision-making.

Western strategic thinking often falls into a binary trap - interpreting Middle Eastern actors as either impulsively aggressive or passively withdrawing. In Shiite theological-political thought, both action and restraint are part of the same strategic framework. What appears as patience may be preparation; what seems like passivity might be purposeful waiting.

Tolik is a Middle East analyst and media professional with extensive experience in covering regional geopolitical developments. His background spans analytical journalism, media production, and strategic communications, having contributed to major Israeli and international television networks and newspapers.